We’re back with Part 2 of oqur breakdown of Insanely Simple: The Obsession That Drives Apple’s Success. If you missed Part 1, you can find it here →

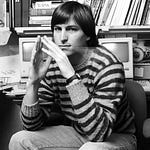

"Simple can be harder than complex. You have to work hard to get your thinking clean, to make it simple. But it's worth it in the end, because once you get there, you can move mountains." — Steve Jobs

To Steve Jobs, simplicity was a religion. It was also a weapon. Revolution after revolution, Jobs proved that Simplicity is the most powerful force in business. It guides the way Apple is organized, how it designs products, and how it connects with customers.

As ad agency creative director, Ken Segall played a key role in Apple's resurrection after Steve Jobs returned. He helped create such marketing campaigns as Think Different. By naming the iMac, he also laid the foundation for naming waves of i-products to come.

Now Segall puts you inside a conference room with Jobs and on the receiving end of his midnight phone cals. You'll understand how his obsession with Simplicity helped Apple perform better and faster, sometimes saving millions in the process.

You'll also learn the ten elements of Simplicity that have driven Apple's historic success — which you can use to propel your own organization.

Sections:

Harnessing the Power of Simplicity

Principle: Think Phrasal

Principle: Think Casual

Principle: Think Human

Principle: Think Skeptic

Principle: Think War

Principle: Think Different

My Highlights & Takeaways

Who is Ken Segall?

See also…

Harnessing the Power of Simplicity

Think Brutal. No need to be mean, just brutally honest—and avoid the partial truths while you're at it. Ask those you interact with to do the same. People will be more focused, more positive, and more productive when they don't have to guess what you're thinking. Positive or negative, make honesty the basis of all interactions. You'll avoid wasting valuable time and energy later.

Think Small. Swear allegiance to the concept of small groups of smart people. Remember it well when new project groups are formed. This is a key component of Simplicity, and you must become its champion. Small groups of smart people deliver better results, higher efficiency, and improved morale, Also, look suspiciously at any project plan that doesn't include the regular participation of the final decision maker. It's critical. Having the decision maker appear at the very end of the process to say yea or nay is a recipe for frustration and mediocrity.

Think Minimal. Be mindful of the fact that every time you attempt to communicate more than one thing, you're splintering the attention of those you're talking to—whether they're customers or colleagues. If it's necessary to deliver multiple messages, find a common theme that unites them all and push hard on that idea. You want people to remember what you say—and the more you cram into your communication, the more difficult you make it for them. Remember that a sea of choices is no choice at all. The more you can minimize your proposition, the more attractive it will be.

Think Motion. The perfect project timeline is only slightly less elusive than the Holy Grail. It takes some effort to figure it out, but once you do, you'll have created a template that promotes success. You may not be the person tasked with creating timelines, but you can try to influence those who are. This is the kind of thing that most people just accept, but they shouldn't. The right timing is as important as the right people. Always be wary of the "comfortable" timeline—it's just a fact of life that a degree of pressure keeps things moving ahead with purpose. With too much time in the schedule, you're just inviting more opinions, and more opportunities to have your ideas nibbled to death. Keep things in motion at all times.

Think Iconic. Even if you're not in the marketing biz, it will serve you well to crystallize your thinking by leveraging an image that can symbolize your idea, or the spirit of it. And if you are in the marketing business, you're simply required by law to think this way. Whatever presentations you make, whatever products you sell, whomever you're trying to convince—never forget the power of an image to galvanize your audience. Note that there's a big difference between finding a great image and decorating a PowerPoint presentation. There's too much decorating in the world already, and for the most part it's meaningless. Find a conceptual image that actually captures the essence of your idea. Be simple and be strong.

The same principle applies whether you're talking to colleagues or to the public. Over time, a conceptual image gives people an easy way to identify your company, your idea or your product. Memorable images often communicate more effectively than words—which is why those who value Simplicity tend to rely on them.

Think Phrasal. This is an area where just about every business needs more work. Words are powerful, but more words are not more powerful—they're often just confusing. Understand that in your company's internal business and in communications with your customers, dissertations don't necessarily prove smarts. In fact, they tend to drive people away.

Though many writers never seem to grasp the point, using intelligent words does not necessarily make you appear smarter. The best way to make yourself or your company look smart is to express an idea simply and with perfect clarity. No matter who your audience is, it's more effective to communicate as people do naturally. In simple sentences. Using simple words. Simplicity is its own form of cleverness—saying a great deal by saying little.

Apple's website is a primer for intelligence in communications. There is a cleverness in writing that runs throughout, but much of the feeling of Apple's "smarts" comes from its brevity and straightforward-ness. In a world where too many people are trying too hard, Simplicity can be extremely refreshing.

The same can be said for product naming. Simple and natural names stick with people, while jargon and model numbers do not. If you wish people to form a relationship with your product, it needs a name people can naturally associate with. Product naming is one area in which Simplicity pays immediate returns.

Think Casual. Do what Steve Jobs did: Shun the trappings of big business. Operating like a smaller, less hierarchical company makes everyone more productive—and makes it more likely that you'll become a bigger business. Choreographed meetings and formalized presentations may transfer information from person to person, but they neither inspire nor bring a team closer together. Embrace the fact that you'll get more accomplished when you converse with people rather than present to them. You'll still have plenty of opportunities to dress up and do things the old-fashioned way. But internally, and on a day-to-day basis with your clients—de-formalize.

Many great creative ideas are actually born in these types of briefings, when key words or phrases emerge in conversation. Some of the agency's most compelling words for Apple were generated this way. If you want to reap the benefits of Simplicity, think big—but don't act that way. As Steve Jobs proved, one of the most effective ways to become a big business is to maintain the culture of a small business.

Think Human. Unless you're in the business of sterilizing things, business is no place to be sterile. Have the boldness to look beyond numbers and spreadsheets and allow your heart to have a say in the matter. Bear in mind that the intangibles are every bit as real as the metrics— oftentimes even more important. The simplest way—and most effective way-to connect with human beings is to speak with a human voice. It may be necessary in your business to market to specific target groups, but bear in mind that every target is a human being, and human beings respond to Simplicity.

Think Skeptic. Expect the first reaction of others to be negative. The forces of Complexity will inevitably tell you that something can't be done, even if the truth is that your request simply requires extra effort.

You'll probably achieve better results if you believe more in the talent of people to work miracles than in those who are quick to provide negative answers.

Don't allow the discouragement of others to force compromise upon your ideas. Push. If you can't get satisfaction with one person or vendor, move to another. If there was one area in which Steve Jobs had a well-deserved reputation for being impossible, this was it. He was relentless about executing ideas and demanding that people perform.

Take pride in your independence and objectivity too. See facts and opinions in context. Definitely consider the expertise of those who provide counsel, but evaluate those opinions against things that may be beyond the expert's vision-like your long-term goals. Steve Jobs knew that the short-term cost, even if it's large, is often outweighed by the future benefit. Real leaders have the ability to grasp the context and decide accordingly. Simplicity isn't afraid to act on Common Sense, even when it runs counter to an expert's opinion.

Think War. Extreme times call for extreme measures. When your ideas are facing life or death, that's an extreme time. Like a soldier in battle, you can't afford to suffer even a single hit—so make sure you hit first. Pull out all the stops. Remember, when your idea's life is on the line, the last thing you want is a fair fight. Use every available weapon. If possible, grab the unfair advantage. And never forget what might well be your most effective weapon: the passion you feel for your idea.

Think Phrasal

My highlights and notes from the chapter on why it's important to Think Phrasal.

The incredible story of naming the iMac and created the “i” naming framework that would become Apple’s hallmark.

Incredibly enough, it all started by trying to beat the name Steve originally gave to the iMac: MacMan.

“We already have a name we like a lot, but I want you guys to see if you can beat it,” said Steve. “The name is ‘MacMan.”

While that frightening name is banging around in your head, I’d like you to think for a moment about the art of product naming. Because of all the things in this world that cry out for Simplicity, product naming probably contains the most glaring examples of right and wrong.

Phil Schiller, Apple’s worldwide marketing manager, was in the room, and Steve revealed that “MacMan” was Phil’s contribution.

“I think it’s sort of reminiscent of Sony,” said Steve, referring of course to Sony’s legendary Walkman line of personal music players. “But I have to tell you, I don’t mind a little rub-off from Sony. They’re a famous consumer company, and if MacMan seems like a Sony kind of consumer product, that might be a good thing.”

Before we left the premises, Steve threw out some guidelines for our naming development.

“First of all, you have to know it’s a Mac,” he said. “So I think it has to have the ‘Mac’ word in it.” This was priority number one, because looks aside, it was a Max through and through, running all the same software.

Steve had two warnings for us, though — two traps he didn’t want us to fall into.

“This is a full-powered Mac, but some people are going to look at it and think it’s a toy. So the name shouldn’t sound too frivolous,” he said.

“There‘s also a danger people might think it’s a portable, because it’s got this big handle on top. But this thing is heavy. That handle is just there to make it easier to move around in the house. So don’t make it sound portable,” he said.

We’d gone through a long list of candidates, trimmed it down to five favorites, and created a single poster board for each. Each board presented a name in big, juicy type, along with a short list of bullet points that described its virtues.

Our favorite name was one that I’d come up with early in the process: “iMac.” It seemed to solve all the problems at once. It was clearly a Mac. The i conveyed that this was a Mac designed to get you onto the Internet. It was also a perfectly succinct name — just a single letter to the word “Mac.” It didn’t sound like a toy and it didn’t sound portable.

We'd gone through a long list of candidates, trimmed it down to five favorites, and created a single poster board for each. Each board presented a name in big, juicy type, along with a short list of bullet points that described its virtues.

Our favorite name was one that I'd come up with early in the process: "iMac" It seemed to solve all the problems at once. It was clearly a Mac. The i conveyed that this was a Mac designed to get you onto the Internet. It was also a perfectly succinct name — just a single letter added to the word "Mac." It didn't sound like a toy and it didn't sound portable.

Using the word "Mac" in the product name was more of a revolution than you might realize. At that time, "Macintosh" had yet to be shortened to a more colloquial "Mac" in the name of any Apple computer. For Simplicity and minimalism, "iMac" seemed to be perfect.

And of course, there was also one other small advantage that came with the name "iMac." It created an interesting foundation upon which Apple could name future consumer products. Maybe, possibly, somehow, some-time, Apple would see fit to create another "i" product?

A week later, we'd generated another batch of names. We threw out all the previous names but left "iMac" in the mix, despite the fact that Steve had used the "hate" word. In this presentation, I relied on a philosophy I learned long ago from a wise man in advertising. It was "As long as you've got new ideas to share, you are free to re-present the old one."

Back in Cupertino for presentation number two, I walked Steve through the new names first. After I'd gone through the new list, he still didn't like any. That's when I pulled out "iMac" again and told him we still had a lot of heart for that one. Steve gave it the courtesy of a fresh look.

"Well, I don't hate it this week," he said. "But I still don't love it. Now we've only got a couple days left, and I still think 'MacMan' is the best name we have."

I'd like to say that there was some big turnaround after this point, one moment of glory that had us all high-fiving one another, but there was not. The very next day, while talking to one of my Apple clients, I learned that there was action on the naming front. Steve was making the rounds asking people what they thought of "iMac." He'd had the name silk-screened onto a model to see how it looked.

I never heard another peep about this decision. Steve basically took it and ran. Obviously he liked what he saw when he got the model back, and he must have received positive reactions from his inner circle.

And so, "iMac" it was.

This, of course, says an interesting thing about the way Steve Jobs worked: He had an opinion. A very strong opinion. The kind of opinion that might knock you over and kick you a few times. But that's not to say he wasn't reasonable or wouldn't ultimately change his mind if confronted with heartfelt opinions presented with passion.

This was a key moment for Apple, when its love of Simplicity won the day and set it on a course it follows to this very day. Steve was unrelenting in his desire to give this great product a great name. He appreciated the power of words. In this case, he appreciated the power of a single letter.

And that little letter "i" became one of the most important parts of the Apple brand.Beyond Common Sense, Apple's approach to naming embraces the concept of consistency. Its computers are all Macs, all the time: iMac, Mac Pro, MacBook Air, and MacBook Pro. The "i" identifies Apple's consumer devices, and is always attached to a word that's descriptive of the product or product category. The naming structure across Apple's major product lines is easy for current and potential customers to understand. And every time you say the name of an Apple product, you know it's an Apple product. That's an incredibly powerful concept, as simple as simple gets — but few companies manage to achieve that kind of branding power in their product names.

New models of iPhone have come out annually since 2007, but each and every one carries the same name. Modifiers exist to distinguish between models (3GS, 4, 4S,s, etc.), but such references are used only when conversationally necessary. Again, people will say, "I'll look it up on my iPhone" but rarely "I’ll look it up on my iPhone 4."

With several distinct shapes, iPod has its own naming story. Unlike the different models of iPhone, which all have a similar use, the different models of iPod have very different uses.

There's iPod touch for an iPhone-like experience with email and apps; iPod nano for full-featured portability; and iPod shuffle — featherweight, screen-less and ideal for working out. But even with distinct names for different models, iPod naming is based in Common Sense, with monikers that are descriptive of each model's size or purpose.

There are no arcane number-and-letter schemes. There are simply "touch," "nano," and "shuffle." These names themselves have become part of the customers vocabulary — single words that are easily remembered.Apple doesn’t just keep naming simple for the sake of brand-building. It keeps naming simple so it doesn’t confuse the hell out of people.

Apple is unrelenting about sending the message of Simplicity to its customers. It does that with every product it creates — and every word it chooses.

Think Casual

My highlights and notes from the chapter on why it's important to Think Casual.

Simplicity is in a hurry. It wants to cut to the chase and concentrate on the important stuff. No insult to you and all the time you’ve spent preparing that convincing speech, but much of what you’re about to say is likely superfluous.

Many people incorrectly assume that by increasing the word count they will demonstrate their smarts, when the opposite is almost always closer to reality. Those who know how to communicate with brevity are the ones who come across as smarter and are more appreciated by executives who value their time.

Think Human

My highlights and notes from the chapter on why it's important to Think Human.

The technology that drives Apple devices is incredibly complex. One with technical expertise could write dissertations describing how these simple" devices do what they do.

But Apple never will. It prefers to speak in more human terms.

Apple didn't describe the original iPod as a 6.5-ounce music player with a five-gigabyte drive. It simply said, "1,000 songs in your pocket." This is the way human beings communicate, so this is the way Apple communicates.Human-speak is a hallmark of Simplicity. It's the recognition that the best way to connect with people is to put things in human terms and use the words that people use in everyday conversation.

This human way of speaking became Apple's trademark at the very beginning. Despite the fact that Apple's products were pure technology-assemblages of circuit boards, buttons, and enclosures, Apple made it clear that they were made for ordinary people who wanted to do extraordinary things. It took something that was inherently complicated and turned it into something that was wonderfully simple.

Even during stages in its past when Apple rarely used imagery of human beings, it was widely regarded as the most human technology company on earth. Its humanity was achieved primarily through "intelligent wit." Here we must give credit to former Chiat creative director Steve Hayden, who led the charge on the original Macintosh. Students of advertising would do well to go back and read the ads Hayden wrote in the early days of Macintosh. He gave Apple a voice that was distinct, simple, and seemingly everlasting.

Apple isn’t interested in ideas that try to please everyone. Those are the ideas that end up stripped of their character, feeling calculated and worst of all less human.

Think Skeptic

My highlights and notes from the chapter on why it's important to Think Skeptic.

During my earliest days working on Apple's advertising, back when John Sculley was CEO, one of the agency's writers created a sign to hang over his office door.

It read: When® lawyers™ roamed* the† earth!™

Standing Up for Details

People often talk about the "unboxing experience" that comes with buying an Apple product. YouTube has countless videos documenting, step by step and piece by piece, the opening of an Apple product box. To the outsider, this is simply another example of Apple fanboy-ism. It's just a box, right?

To Apple, a box is hardly "just a box." The company takes incredible care to ensure that the entire customer experience is consistently first quality. And that first moment, when the customer is going through the packaging, is a significant part of that experience.

Apple's singular obsession: the customer experience.

If there is one focus at Apple that transcends all others, it's the customer experience. The goal is to give the customer a consistently great experience throughout their entire relationship with Apple. From TV ad and website to shopping to unboxing to everyday use to repair and support, Apple aims to consistently deliver the same values and speak in the same tone.

Think War

My highlights and notes from the chapter on why it's important to Think War.

It must become your nature never to relent.

Every new plan and every new idea needs to break through a layer of resistance.

Think Different

My highlights and notes from the chapter on why it's important to Think Different.

In an interview, Steve Jobs once said: “Sometimes when you innovate, you make mistakes. It is best to admit them quickly, and get on with improving your other innovations.”

Steve Jobs was a firm believer in the concept of the "brand bank."

He believed that a company's brand works like a bank account. When the company does good things, such as launch a hit product or a great campaign, it makes deposits in the brand bank. When a company experiences setbacks, like an embarrassing mouse or an overpriced computer, it's making a withdrawal. When there's a healthy balance in the brand bank, customers are more willing to ride out the tough times. With a low balance, they might be more tempted to cut and run.

Having a high balance in the brand bank makes all the difference.

My Highlights & Takeaways

Steve Jobs taught us many things. But perhaps his most timeless lesson was in the power of simplicity.

Apple wielded simplicity. Using it to ship breathtaking products, enter new markets, and build magically simple software.

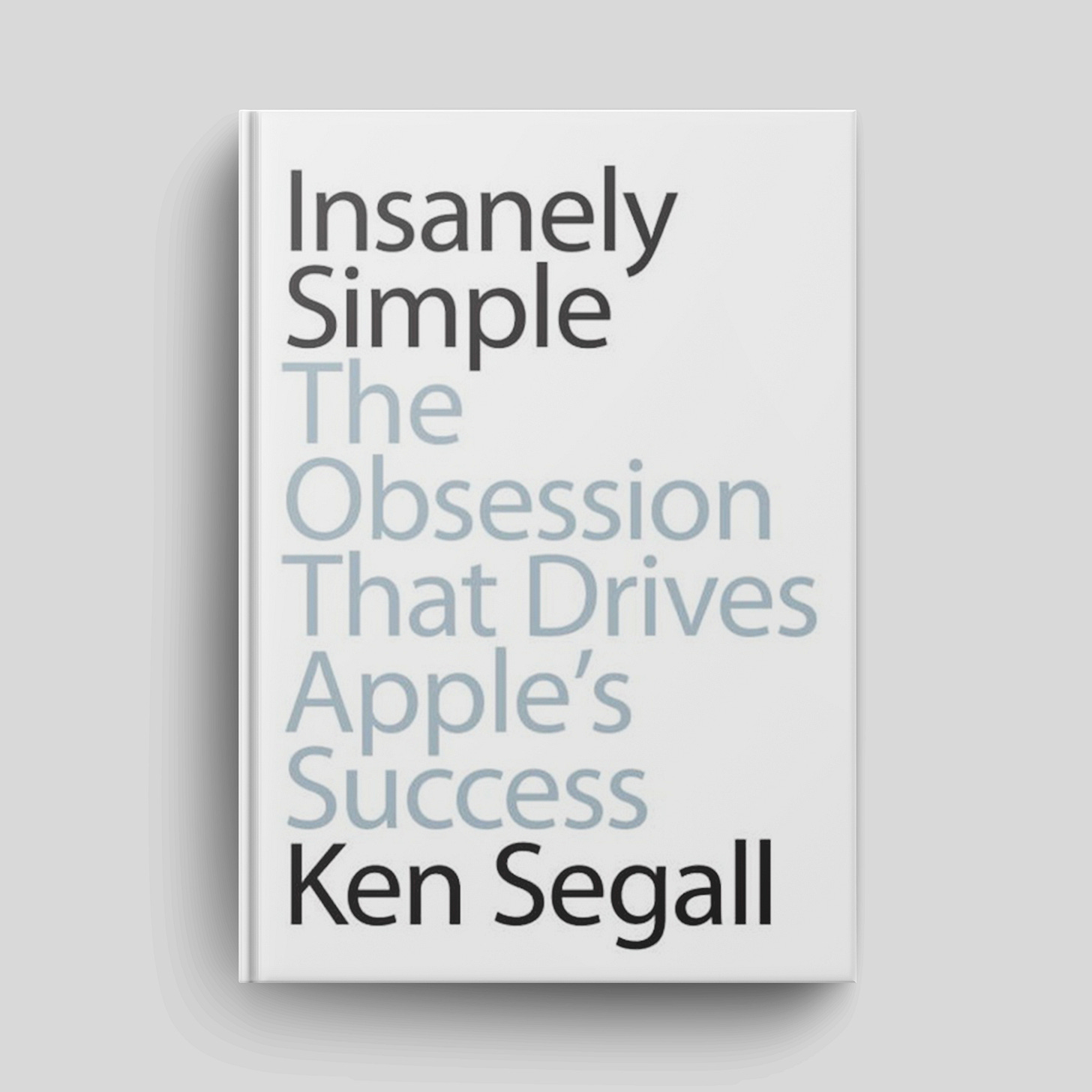

The best study on Apple’s approach to simplicity is “Insanely Simple: The Obsession That Drives Apple’s Success” by Ken Segall.

Here are my favorite ideas from the book:

As those who worked at Apple will attest, the simpler way isn’t always the easiest. Often it requires more time, more money, and more energy.

Every one of Apple’s revolutions was both of the company’s devotion to Simplicity. Apple’s goal with every product is to make something “simple amazing, and amazingly simple.”

Simplicity not only enables Apple to revolutionize. It enables Apple to revolutionize repeatedly.

As Simplicity becomes more rare, it also becomes more valuable. So your ability to keep things simple, and protect things from becoming more complicated, becomes more valuable as well.

Complexity, unfortunately, is part of the human condition. It lives inside all of us — yes, including people like Steve Jobs. By the end of the book, you’ll see that even Steve, champion of Simplicity, was perfectly capable of lapsing and falling victim, if only momentarily, to the Complexity within.

Simplicity doesn’t spontaneously spring to life with the right combination of molecules, water, and sunlight. It needs a champion — someone who’s willing to stand up for its principles, that’s strong enough to resist the overtures of Simplicity’s evil twin, Complexity.

Steve wielded “The Simple Stick” and always rejected work that failed to distill an idea down to its essence. He hated work that took a turn when it should have traveled in a straight line.

Clarity propels organizations. Not occasional clarity but pervasive, twenty-four-seven, in-your-face, take-no-prisoners clarity. Steve demanded straightforward communication from others.

“Good enough is not good enough.” Settling for second best is a violation of the rules of Simplicity, because it plants the seeds for disappointment, extra work, and more meetings. Your challenge is to be unbending when it comes to enforcing your standards. Mercilessly so.

In Apple’s world, every manager has to be a ruthless enforcer of high standards.

Apple encourages big thinking but small everything else. Small working teams. Small groups of approvers. Small meetings with only those essential in attendance. No “mercy invitations.” No spectators. Either you’re critical or you’re not.

To say that putting more people on a project will improve the results is basically saying that you don’t have confidence in the group you started with. Either that or you’re just looking for an insurance policy — which also means you don’t have a lot of confidence in the group you started with. What you’re really saying is that you don’t have the right people on the job. So fix that.

When process is king, ideas will never be.

Mark Parker, when he was President and CEO of Nike, once asked Steve for advice. Steve hit him with the simple stick: “Nike makes some of the best products in the world — products that you list after, absolutely beautiful, stunning products. But you also make a lot of crap. Just get rid of the crappy stuff and focus on the good stuff.”

Steve looked at pretty much everything with the idea of cutting it down to its essence, whether it was a new product or a new ad. He had an instant allergic reaction to any suggestions that might add complication.

Human beings are a funny lot. Give them one idea and they nod their heads. Give them five and they simply scratch their heads. Or even worse, they forget you mentioned all those ideas in the first place.

People will always respond better to a single idea expressed clearly. They tune out when Complexity begins to speak instead.

When in doubt, minimize.

Apple’s advertising strategy can be boiled down to one sentence: Saying fewer things in more important places.

Apple rigidly enforces the principles of Simplicity whenever it speaks to its customers. Most of its product ads simply show a brief demonstration of the device.

The technology that drives Apple devices is incredibly complex. But Apple prefers to speak in human terms. Apple didn’t describe the original iPod as a 6.5-ounce music player with a five-gigabyte drive. It simple said, “1,000 songs in your pocket.” Human-speak is a hallmark of Simplicity. It’s the recognition that the best way to connect with people is to put things in human terms and use the words that people use in everyday conversation.

Who is Ken Segall?

The author of the this book, Ken Segall, worked closely with Steve Jobs as ad agency creative director for NeXT and Apple. He was a member of the team that created Apple’s legendary Think different campaign, and he’s responsible for that little “i” that’s a part of Apple’s most popular products — having created the original name iMac that introduced this naming convention. Segall has also served as creative director for IBM, Intel, Dell, and BMW.

See also…

For more on Steve Jobs, check out the following:

Book Breakdown: “Insanely Simple: The Obsession That Drives Apple's Success”

Book Breakdown: “Finding the Next Steve Jobs: How to Find, Keep, and Nurture Creative Talent”

Hope you enjoy this breakdown,

Daniel Scrivner

Founder of Ligature: The Design VC

P.S. Watch this episode

You can also watch me break down this essay on YouTube and subscribe so you never miss a video.

Share this post